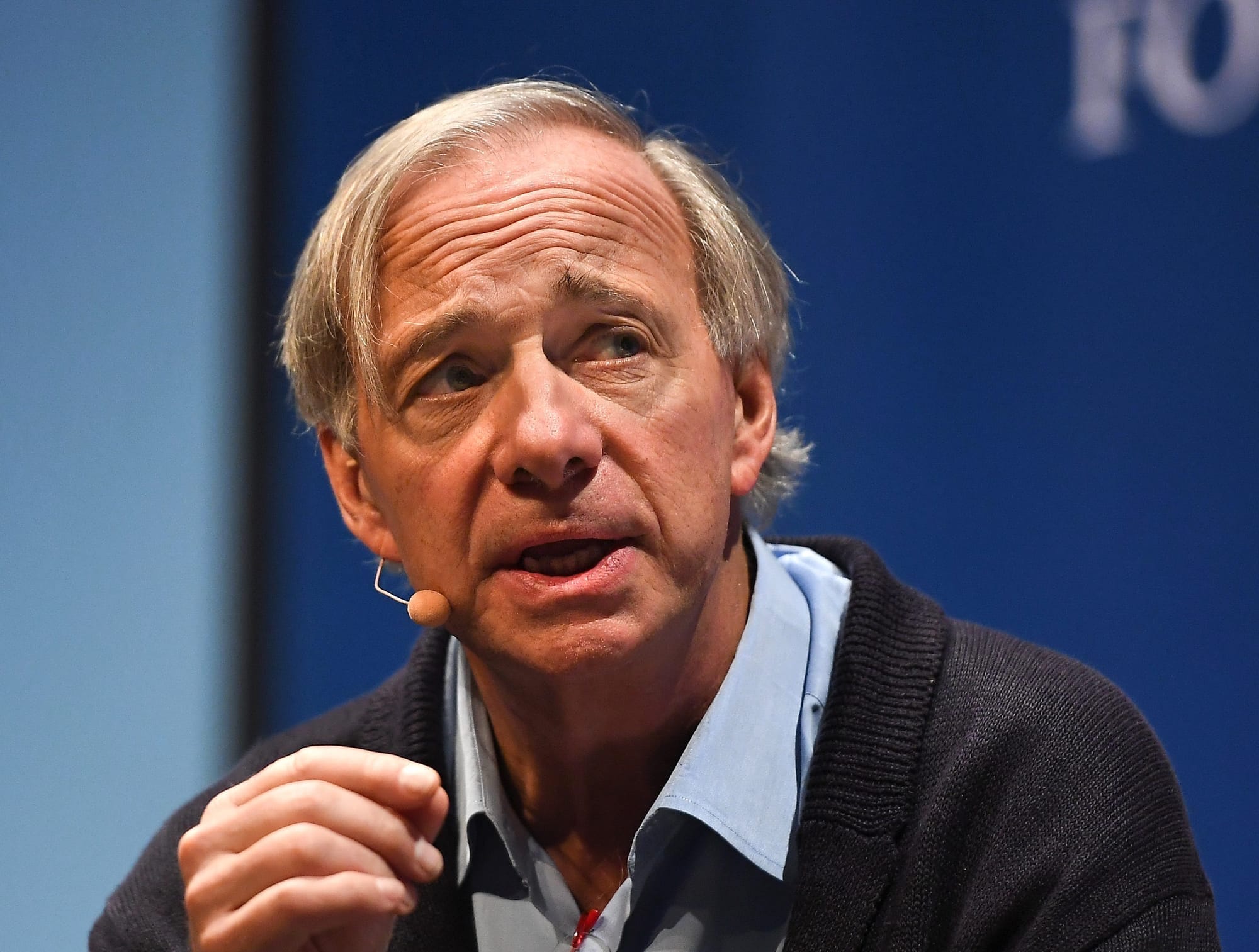

Ray Dalio wears a permanently concerned look on his face. Now 76 years of age, this gaze comes from a lifetime of doubting what he has been told in his long rise to the top. When out of his Connecticut home he often pairs a dress shirt and a carefully curated cardigan that matches his curious eyes, with which he stares into the future of the world’s economic system and theorizes the possible profit from its downfall.

It is these well-timed premonitions of doom and successes that have allowed him to rise out of his humble origins in Queens. He used networking and grit to carve a path into Harvard Business School. He used these skills to turn a hardly-formalized financial group named Bridgewater which ran out of his apartment into the world's largest hedge fund with a mind-numbing $160 billion under his management. And even in retirement he currently sits on top of the world of economic thought with his predictions moving global markets daily and a wave of his finger sending butterfly effects around the world.

So, how do you become a billionaire?

Here’s Ray’s way:

Raymond Thomas Dalio, Born on August 8, 1949, in Queens, New York City to an Italian saxophone player and a homemaker. The family uprooted and moved to Long Island when Ray was eight. He found his way into the world of high finance through a friend whose parents golfed at The Links, a prestigious club frequented by many wealthy members. Dalio picked up a summer caddying job and made the commute by walking from his house every morning to caddy for the many Wall Street professionals who frequented the greens. It was through these long afternoons of hauling clubs that he met Mr George Leib, a longtime chairman of Blyth and Co., a prestigious investment bank. Dalio would often come to the Leib’s home for dinners and holiday events that were attended by the who’s-who of Wall Street, many of whom would meet Dalio at these functions. Leib's son would soon offer Dalio his first job on Wall Street, giving him a summer internship at his firm. After this, Dalio pursued a bachelor's degree in finance at Long Island University, then after graduating he became a clerk on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange or NYSE. After these experiences he went to college and graduated with an MBA from Harvard, completing his formal education in finance and rocketing him into the real world.

According to an interview with Dalio on CNBC, his early investments were in commodities since they had the lowest barrier to entry, necessary for a humble college student, and he knew this was where he wanted to start his financial journey. After graduating from Harvard, he moved to Connecticut where he traded futures contracts out of a converted barn. He later graduated from the literal bullpen and made it to the figurative one on the floor of the NYSE, where he traded for Dominick and Dominick, later becoming the director of commodities there. He then moved to a higher-profile firm, where he was subsequently fired for punching his boss at a New Year’s Eve party.

This new year also marked Dalio’s new entry into self-employment and a few days after his forced removal, he founded Bridgewater Associates. Originally a small wealth advisory firm ran out of his NYC apartment, mainly consisting of clients he had built up over his time on the street and not punched in the face yet. The company's key selling point was the fabled Daily Observations written by Dalio at the crack of dawn and distributed to his clients before the opening bell; this publication significantly grew Bridgewater’s reach and prestige through Dalio’s insightful observations on the state of the market.

The firm's big break came when they signed McDonald’s as a client. The pension funds for the World Bank and Eastman Kodak followed shortly after. These signings led to massive capital inflows for Bridgewater and gave it immense credibility among its peers. With this backing, Dalio had begun to look at a massive bet, and one that, according to CNBC, other managers would call “plain crazy,” but would ultimately cement him on the global stage of hedge funds. In the five years leading up to 1987, there was one of the strongest bull markets ever seen. The largest indexes over the entire globe rose almost 300% in a short period. Everyone was making a lot of money riding this wave, including Dalio, but he had started to suspect this rise.

With very few indicators leading to the now infamous “Black Monday,” it's undetermined how Dalio had decoded this market mystery. It is still not fully known why this unprecedented drop occurred, but what is known is that on Monday, October 19th, 1987 the US market opened falling and didn’t stop. The bloodbath only came to a halt when trading floors forcibly closed and allowed the markets to stabilize. By the time the clouds had parted the US market was down an unprecedented 22.6%, the single largest one-day drop ever, with almost everyone suffering intense capital losses.

That is, except for Dalio. He had been preaching signs of doom since the mid-1980s, going as far as to testify in front of Congress about his worries concerning a tightening monetary policy and international tensions. This concern had made him very well-positioned for a market crash and allowed him to come out of this dark time practically unscathed.

Dalio followed this impressive feat up with an arguably more impressive one. He appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show and was able to move out of New York City. He settled in Westport, Connecticut, with the fund subsequently following him. This was so he could start a family with his wife of four years, Barbara, who was descended from the Vanderbilt and Whitney dynasties. In 1991, Bridgewater launched the fund it would come to be known for, aptly named Pure Alpha. Alpha, commonly shown by its Greek letter ⍺, is a Wall Street term used to denote the performance of a manager over a correlated index. For example, if the NASDAQ performed 4% up in the year to date and Dalio had made 7%, he would have 3% of alpha. This fund became known for its risky bets and the pursuit of outperformance that led to its steep upward trajectory. Five years later, in 1996, Dalio launched another notable fund, All-Weather which was a risk-averse fund that popularized the now commonly used strategy of risk parity, showing Dalio’s immense influence on “the street.”

Thanks to these funds and other innovations by Dalio, in 2005 Bridgewater became the largest hedge fund in the world, a title it has held since then, showing unprecedented dominance in such a competitive field. The funds had taken on much larger clients since its McDonald’s days, such as the massive California and Pennsylvania State Employees Pension Funds with billions of dollars of investable backing.

With this massive influx of new capital under management, Dalio knew that he needed to do something to prove himself further, and luckily for him, that opportunity was right around the corner. In the early 2000s, the stock market saw a bull run even larger than the one that preceded the crash of 1987, especially in the housing market where loans were given out far too liberally with a ludicrous number of Wall Street bets riding on the repayment of them. According to a 2009 article in Barron's magazine, Bridgewater "began sounding alarms...in the spring of 2007 about dangers of excessive financial leverage" and according to that same article, "nobody was better prepared for the global market crash" than Bridgewater's clients and subscribers to its Daily Observations. Dalio even visited the White House and spoke to many members of the George W. Bush administration at the time about his concerns, but he was largely disregarded. However, Dalio’s pessimism and ability to see through the excessive optimism was about to pay off once again, for himself at least.

When that crash eventually came, Bridgewater largely escaped the wide-ranging effects of it. This was possible as Dalio anticipated that the Federal Reserve would be forced to print a lot of money to revive the economy when the crash came. So he bought large amounts of Treasury bonds, shorted (bet on the price going down) the dollar, and bought gold and other commodities that were seen as “safe havens” by investors, leading to their prices rising in times of turmoil. This success was followed up by John McCain visiting Bridgewater headquarters and speaking to staff on his Presidential campaign.

In 2011, Dalio published a book that would come to define him and change Bridgewater drastically. With the release of Principles, Dalio explained his general philosophy regarding life and investment in a very, very long list of individual “principles” that he lives by. Some of these principles include “Embrace Reality and Deal with It,” “Pain + Reflection = Progress,” and “Radical Truth with Radical Transparency.” The last two especially would come to define Bridgewater’s infamous corporate culture based entirely around radical transparency or (depending on who you ask) overbearing and unnecessary feedback. Mr. Jeff Clarke, a Managing Director of Brookfield Asset Management, says “It works because it's his fund, meaning, if you tried to do it at JP Morgan or UBS or [another bank] it just couldn't work.” These principles have made Bridgewater a place of very high tensions and one that has drawn outside criticism for its promotion of an unhealthy work-life balance, again with Mr. Clarke saying, “These principles work very well for the few people that it works for. It takes a special kind of person to be able to work with them.”

In 2012, Bridgewater soared to new heights, with investments from massive entities like the Texas Teachers Pension Plan, SERS, General Motors, the Government Investment Corporation of Singapore, and other giants of the equity space. Bridgewater was such an attractive investment to these firms because Pure Alpha, Bridgewater's flagship fund, had only three losing years in its entire history and returned an average of 10.4% regardless of overall market volatility, making it one of the best bets these stability and return-driven investment vehicles can make.

In 2017, Bridgewater peaked its valuation and hit an eye-watering 160 billion in assets under direct management, making it worth more than all of the silver in the world. It was at this acme of his career that Dalio announced his retirement and exited the company very ceremoniously on April 5th.

After retiring from the active investment world, Dalio has transitioned to being a philanthropist, TV news talking head, and fierce China advocate. In his 2021 book The Changing World Order, Dalio describes a world that ebbs and flows through economic patterns with the empires’ rise and fall. The main point of this book is that soon, although he doesn’t specify when China will replace the US as the major global power. Coincidentally or not, since the publication of this book Bridgewater, which Dalio is supposedly not involved in anymore, has become the single largest fund buyer of Chinese stocks. Mr. Charles Holt, a Managing Partner at Verdence Capital Advisors, believes that “This will likely be Dalio’s largest influence, his doubt of the US Economy and strong belief in China will come to define him, and we’ll see if he’s right or not.” It is this “great replacement” and general economic pessimism that Dalio frequently advocates for on the many cable news networks that will take him. As one could expect, he has been making many appearances since the tariff crisis, saying in a CNN article on April 30 that “it is too late to combat the economic fallout of Trump’s tariffs and the world economic order, with the US at the center, is breaking down.”

It’s that well-timed pessimism that got Dalio where he is today. He didn’t coast through economic booms but braced for their collapse and called them before anyone else. His story is one of relentless belief in cycles - economic, political, personal - and a faith in his own intuition, fortified by obsessive research. From humble beginnings carrying golf bags to managing $160 billion and becoming a global economic force, Dalio built a legacy out of doubting the consensus and preparing for disaster. Love him or hate him, his influence hasn’t faded in retirement. Whether through Bridgewater’s continued plays, his ever-present media appearances, or his infamous “principles,” Ray Dalio remains exactly what he’s always been: cardigan-clad, concerned, and convinced that the next crash is already unfolding.